Guest Blogger: Jonathan Martinis, Esq., J.D., Rethinking Guardianship Consultant

What’s your favorite right? What’s the right that makes you proudest, the one you’d fight for if someone tried to take it away? Is it freedom of speech? Voting? Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness?

What do these and all our other basic and bedrock rights have in common? Choice. Without choice, we have no rights. Choice gives us the power to decide what to say and keep secret, who governs us, and how, where, and with whom we live, work, and play. By choosing – even when others may disagree with our decisions – we assert our independence and honor those who marched, fought, voted, and taught to ensure that we have choices to make.

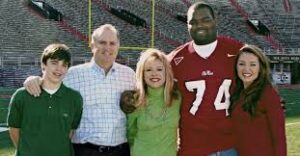

Britney Spears and Michael Oher should make us think about how fragile our rights and choices are. Both were court-ordered into conservatorship (called “guardianship” in most states) and lost their right to make fundamental choices about their lives. They, like millions of others, became “wards,” with their appointed conservators given “substantial and often complete authority over [their] lives.”[1] Both have been in the news because, after more than a decade in conservatorship, they fought to regain the rights they lost, and made us wonder whether they should have lost their rights in the first place.

When people truly cannot make decisions and direct their lives, guardianship and conservatorship can be helpful or even life-saving. However, research and scholarship show that, if people can make choices, by themselves or with support, taking away their legal right to do so can cause “significant negative impacts on physical and mental health, longevity, ability to function, and reports of subjective well-being.” [2]

This is not a new concern. Decades before the #FreeBritney movement, Congress found that “the typical ward has fewer rights than the typical convicted felon” and called guardianship and conservatorship the “most punitive civil penalty that can be levied against an American citizen, with the exception . . . of the death penalty.”[3] Since then, study after study has found that older adults and people with disabilities who make more decisions and exercise more control over their lives – who have more self-determination – have a better quality of life.[4] A recent national study found that, among people with disabilities who had similar abilities and limitations, those that did not have guardians were more likely to live independently, work, have friends, and be active in their communities than those with guardians.[5] In just the last ten years, since I had the honor of representing a young Virginian named Jenny Hatch in the first trial holding that a person had the right to use an alternative called Supported Decision-Making instead of being ordered into a permanent guardianship,[6] over 20 states have changed their laws to recognize and prefer such alternatives, when appropriate, over guardianship and conservatorship.[7]

Even still, at a time when there are more laws, supports, services, and technology designed to enhance our independence than ever before, the estimated number of adults in guardianship and conservatorship has tripled since 1995.[8] And even though most state laws say that guardianships and conservatorships should be limited and remove only the rights that people cannot exercise, a study found that over 90% remove all rights.[9] Most disturbingly, research has documented a “school to guardianship pipeline” funneling young adults with disabilities into legal dependency and loss of rights from which the vast majority will never return.[10]

Why? Guardianship was originally envisioned as a last resort. Almost all state laws say that people should not be ordered into guardianship unless they are “unable” or “incapable” of making decisions and, even then, only if there are no less-restrictive alternatives available.[11] Nevertheless, the sad but true fact remains: laws alone don’t and can’t change minds or behavior – if they did, no one would speed.

Despite laws and policy, research, best intentions and practices, people like Michael Oher, Britney Spears, and countless others who aren’t celebrities, will continue to be ordered into guardianship every day unless we ask ourselves the question I began with: what’s your favorite right? Then, and only then, will we realize that we’re all only one accident, stroke, or diagnosis, and one well-meaning (or not) family member, friend, or stranger away from losing it, from having “fewer rights than a convicted felon.” Then we can begin asking questions before seeking guardianship or conservatorship like, “What else have we tried? What else could we try to help this person without taking away their rights?” Maybe alternatives like Supported Decision-Making, Powers of Attorney, or Psychiatric Advance Directives would work for the person and improve their quality of life. Maybe they won’t and guardianship or conservatorship will be appropriate.

If we don’t ask those questions now – if we don’t make sure that guardianship and conservatorship are the last resorts they’re meant to be – who is going to ask them when we need help?

[1] Judge David Hardy, Who Is Guarding the Guardians? A Localized Call for Improved Guardianship Systems and Monitoring, 4 NAELA J. 1, 7 (2008).

[2] Wright JL. Guardianship for your own good: Improving the well-being of respondents and wards in the USA. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2010 Nov-Dec;33(5-6):350-68.

[3] H.R. Rep. No. 100-641, at 1 (1987).

[4] E.g., g., Karrie A. Shogren et al., Relationships Between Self-Determination and Postschool Outcomes for Youth with Disabilities, 4 J. Special Educ. 256 (2015); Laurie Powers et al., My Life: Effects of a Longitudinal, Randomized Study of Self-Determination Enhancement on the Transition Outcomes of Youth in Foster Care and Special Education, 34 Child. & Youth Services Rev. 2179 (2012); Janette McDougall et al., The Importance of Self-Determination to Perceived Quality of Life for Youth and Young Adults with Chronic Conditions and Disabilities, 31 Remedial & Special Educ. 252 (2010); Ishita Khemka et al., Evaluation of a Decision-Making Curriculum Designed to Empower Women with Mental Retardation to Resist Abuse, 110 Am. J. Mental Retardation 193 (2005)

[5] Bradley, V. J., Hiersteiner, D., Li, H., Bonardi, A., & Vegas, L. (2020). What Do NCI Data Tell Us About the Characteristics and Outcomes of Older Adults with IDD? The Developmental Disabilities Network Journal, 2(2), 50–69.

[6] Www.jennyhatchjusticeproject.org

[7] National Resource Center for Supported Decision-Making (n.d.) In your state. https://supporteddecisionmaking.org/in-your-state/

[8] See, Windsor C. Schmidt, Guardianship: Court of Last Resort for the Elderly and Disabled. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press (1995); Sandra L. Reynolds, Guardianship Primavera: A First Look at Factors Associated with Having a Legal Guardian Using a Nationally Representative Sample of Community-Dwelling Adults. 6 Aging and Ment. Health, 109-120 (2002); Brenda K. Uekert, Richard Van Duizend, R., Adult Guardianships: A “Best Guess” National Estimate and the Momentum for Reform. In Future Trends in State Courts 2011: Special Focus on Access to Justice (2011).

[9] Pamela Teaster, et al., Wards of the State: A National Study of Public Guardianship. Stetson Law Review, 37, 193-241 (2007).

[10] National Council on Disability. New Federal Research Examines Guardianships of People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, finds School to Guardianship Pipeline. (2019) Available at: https://ncd.gov/newsroom/2019/new-federal-research-examines-guardianships

[11] Martinis, J., Harris, J., Fox, D., & Blanck, P. (2023). State guardianship laws and supported decision-making in the United States after Ross and Ross v. Hatch: Analysis and implications for research, policy, education, and advocacy. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 34(1), 8-16.